In a small room at the QEII’s Nova Scotia Rehabilitation and Arthritis Centre, there sits a machine similar in shape to an easy bake oven, but the goodies it dispenses are considerably more practical than they are edible.

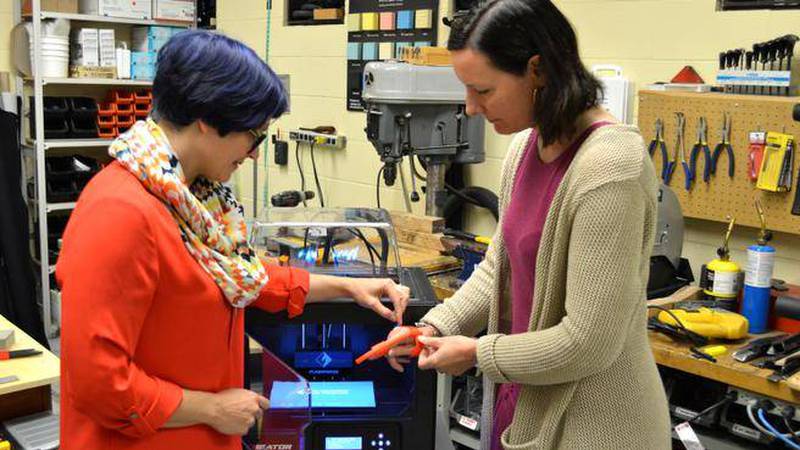

For two years now, staff and patients alike have been aided by this humble box, a 3D printer which translates lifeless computer code into tangible objects. It needs only the heated plastic with which it works and the thoughtful requests of occupational therapists like Cher Smith.

“We’re still learning all the things it can do,” she says. “The more successes we have, the more we realize how helpful it will be to our clients.”

Cher dedicates herself to the seating and mobility needs of patients unable to walk, spending much of her time with those for whom off-the-shelf equipment simply won’t work. With the help of technicians and fellow occupational therapists, she specializes gear to meet the individual needs of her patients, an exercise in problem solving if ever there was one.

A machine converting ideas into objects has great utility in a situation like this. Kim Parker is a mechanical engineer responsible for supporting staff of the Rehabilitation Centre wherever technology is concerned, including the 3D printer.

Should patients need a mount for their wheelchair or a lengthened joystick to compensate for loss of fine motor control, there are freely available design files available to be printed. But if a patient’s situation calls for something more specialized, these rehab staffers must take matters into their own hands and use design software to create objects from scratch.

Cher describes a young man who survived a severe brain trauma and is unable to walk or to open his hand, curled permanently into an awkward fist. This, among other things, prevents him from operating a standard wheelchair joystick. With the aid of playdough, however, Cher was able to mould his joystick a new top fitted neatly to his fist, and with specialized software Kim built the code for a 3D printed version.

In another instance, a woman with muscular dystrophy depends on one hand to manipulate the various controls on her wheelchair, but in winter that hand was prone to freezing outdoors. A warming dome was moulded to snap in place over that hand, converted to code and again, printed into hard plastic. Equipped with rechargeable hand-warmers and polar fleece, this dome made all the difference on those cold winter days. Being a stylish woman, the dome was even overlaid with black leather to match her jacket.

This 3D printer has limits, of course, from the materials it employs to the comparative cost effectiveness of off-the-shelf equipment. It won’t be replacing manufacturers or technicians any time soon, says Kim, but its ability to prototype person-specific gear at relatively low cost is invaluable. In time, both Kim and Cher see 3D printers being used regularly in the world of rehabilitation.

“In 10 or 20 years, I see 3D printers doing a whole lot more,” says Kim.