Minutes and seconds equal precious moments in organ transplantation, so when Dr. Robert Liwski and his team found a way to trim the time it takes to confirm an organ match by 70 per cent, the world listened.

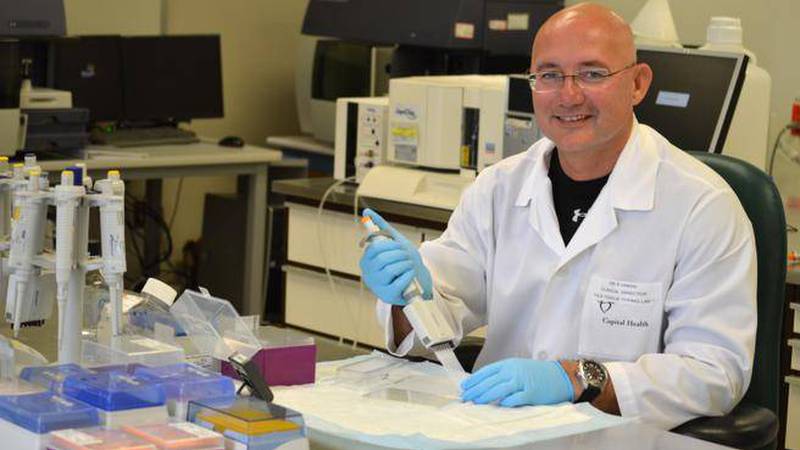

Dubbed the Halifax Protocol, Dr. Liwski, pathologist and director of the Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA) lab at the QEII Health Sciences Centre was motivated to innovate when he realized the original crossmatch protocol had last been updated in 1989.

“The original protocol was reasonably good, but it was time-consuming and cumbersome and you couldn’t perform many crossmatches at the same time,” Dr. Liwski says.

When an organ is donated, the QEII’s HLA lab is tasked with crossmatching the recipient’s serum with the organ donor’s cells to ensure compatibility.

The QEII is the only transplant centre east of Quebec. Dr. Liwski directs the Halifax HLA lab, interprets the results and gives the go-ahead to the QEII transplant team waiting to prep the patient(s) and perform the transplant.

HLAs are the molecules expressed on the cell surface, which are used by the immune system as triggers to start fighting against pathogens, or new organs invading the body. Everyone’s HLA molecules are unique and the molecules vary across ethnic groups. HLA technologists isolate the cells from the donor and mix them with sera from the recipients to check for antibodies against donor HLA antigens. The goal is to find a donor who doesn’t have any HLA antigens the recipient reacts to.

The original tube method crossmatch protocol could take up to seven hours, was susceptible to human error and was limited in the number of tests that could be done at one time. Dr. Liwski was determined to do better.

“The first thing we did was switch from the tube method to the plate method, which means you can really efficiently match many patients against the same donor,” Dr. Liwski says. “Then, we started looking at speeding it all up.”

Under a closer lens, Dr. Liwski’s team discovered that long-held standards like the incubation time for a serum and reagents used in the procedure, were unnecessarily long and complicated. Shortening these incubation times further increased efficiencies in the HLA lab.

“We found on average, we saved a lot of time and because the new protocol is less costly, we also saved a lot of money,” Dr. Liwski says, adding that a reduction of variables from lab to lab led to more consistent results.

As a result, the Halifax Protocol has been adopted by all centres in Canada, more than 30 in the United States, as well as around the world in areas such as Australia, the United Kingdom, France, Brazil, Germany, Poland, and the United Arab Emirates.

HLA labs adopt the protocol and may modify it to meet their unique needs and testing volumes.

Dr. Kathryn Tinckam of Toronto General Hospital says the implementation of the Halifax Protocol in her lab has had a positive impact on patient outcomes and has allowed the lab to perform multiple crossmatches at once.

“When you’re looking at a kidney or heart or lung transplant, those hours saved make a huge difference,” Dr. Tinckam says. “Those minutes add up to the overall quality of the function of the organ for the patient.”

As medical director of the hospital’s HLA lab, and medical advisor to Canadian Blood Services in transplantation, Dr. Tinckam said the new protocol serves as a good reminder of the importance in challenging conventions and pushing for excellence.

Implementing the Halifax Protocol at Toronto General allowed the laboratory to test crossmatches simultaneously and get answers to the clinicians even faster, Dr. Tinckam says.

“What Dr. Liwski was able to show is that we should challenge assumptions and when we do, we can save money, get a transplant done faster and positively impact patient outcomes.”