Jeannine Crenian remembers entering the operating room at the QEII Health Sciences Centre and meeting all of the members of the surgical team. It was June 10, 2021 and she was about to undergo surgery to remove cancerous tumours from her neck.

“All the team members introduced themselves — the anesthesiologists, the nurses and the pathologist — and explained their roles,” she recalls. “They were all really comforting and very professional.”

She was also introduced to da Vinci, Atlantic Canada’s first surgical robot, who would assist Dr. Martin Corsten, QEII head and neck surgeon, in the procedure.

“The team did such a good job,” she recalls. “They found the primary tumour, so I didn’t need to have chemotherapy or radiation.”

Even the most gifted surgeon is limited by the size and mobility of the human hand. The da Vinci robot’s thin mechanical arms — four in total and equipped with a camera — can go where a surgeon’s hands cannot. For head and neck surgery, only three of these robotic arms are used, which Dr. Corsten controls from a nearby console.

“If we can find the primary tumour and remove it with clear margins, the patient usually doesn’t require any radiation therapy,” Dr. Corsten explains.

Atlantic Canada’s first surgical robotics technology was introduced at the QEII in February 2019, and was made possible by a $8.1-million initiative, funded entirely by QEII Foundation donors. The da Vinci robot was first put into service in urology, followed by gynecologic oncology in March 2019.

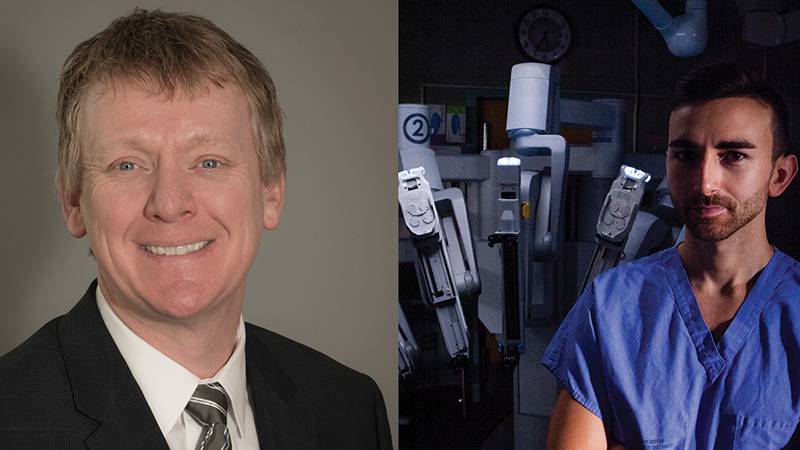

In December 2020, the robotics program was expanded to include otolaryngology (ear, nose and throat) and, since that time, Dr. Corsten has performed approximately 15 robot-assisted operations.

Otolaryngology is particularly well-suited to this technology. Removing a tumour is always a delicate procedure, but tumours located at the base of the tongue and tonsil area present additional challenges.

“These tumours are tucked away ‘around a corner,’ which makes line-of-sight surgery difficult,” Dr. Corsten explains. “Now I can put in a scope that can look up and around that corner, and the robotic arms can operate on the tongue base as if it were right in front of me. This allows me to perform the surgery with improved precision.”

This increased precision and greater magnification results in less bleeding, fewer complications and quicker recoveries for patients.

“Without this increased magnification, a surgeon might cut through a blood vessel and cause bleeding,” Dr. Corsten says. “Now I am able to see the blood vessel in advance, and we can put clips on to prevent bleeding from happening.”

The improved precision comes from the surgeon being able to scale their movements. If the surgeon’s hand moves two centimeters, the robotic arm — with multiple joints providing a far greater range of motion than a human’s — moves just one-third that distance.

Tony Blinkhorn, surgical robotics coordinator at the QEII, probably has more contact with the da Vinci robot than anyone else. He says the experience gained through the urologic and gynecological procedures enabled a seamless transition into ENT surgery.

“With all three services combined, I think we’re approaching 500 cases in total,” Blinkhorn says. “We’ve got some excellent institutional knowledge built up.”

The two standard options for treating oropharyngeal cancers are radiation or surgery, Dr. Corsten explains. “They are both effective, but there are some real advantages to surgery.”

One consideration is that radiation can be used on a particular part of the body just once in a lifetime. Another is that while the side effects of surgery are apparent immediately but improve over time, radiation therapy often does the reverse.

“Radiation tends to have more complications that happen later on,” Dr. Corsten says. “As well, surgery is generally less costly to the healthcare system than radiation, and is performed in one day, while radiation typically requires 33 separate treatments over a number of weeks.”

Having da Vinci in action as part of its surgical robotics offering also helps the QEII teach and recruit talented surgeons, Dr. Corsten adds.

“Teaching surgery can be hard, because you either do it, or you let them do it,” he says. “Now I can have a resident or fellow working on a console beside me. We both have the magnified view, so I can watch what they’re doing, and I’m able to take back control at any time.”

“When we interview medical students who are looking for a residency program, or fellows for a fellowship program, they almost always ask about robotics surgery. It’s so much easier to recruit now that we have a robotics program up and running.”