The ability to drive has quite rightly been equated with freedom. For many Nova Scotians the rhythms of daily life — the commute to work, the gathering of groceries, the visiting friends or the attending classes — begins and ends with the turn of a key. But when someone’s ability to drive safely has changed because of accident or illness, that freedom might be lost. It’s up to the QEII Health Sciences Centre's Driver Evaluation Program to help make that decision.

Occupational therapist Jennifer Mason has worked with this provincial program for 14 years now, literally taking a back seat to people who have had strokes, spinal cord injuries, dementia and more to see if they can still accommodate the rules of the road.

“Research has shown that you cannot anticipate someone’s driving ability with paper and pencil tests,” says Jennifer.

“The gold standard is to actually take someone out for a drive. That’s why these programs exist.”

When someone is referred to driver evaluation by their doctor following a medical event, Jennifer says they still do written tests and other analyses to gauge their physical fitness, reaction time, spatial awareness, concentration and range of motion. But in the end they always hit the road.

While these evaluations might bear superficial similarities to the driving tests of youth, Jennifer is watching with a different lens than the registry. Many of the people she sees are seniors who were never tested with today’s driving standards. She doesn’t necessarily fail people for making mistakes, but instead instructs them on the way it should be done and watches to see if the mistakes are corrected.

It's about separating someone’s bad habits from a fundamental loss of ability.

“What we want to do is get safe drivers back on the road because their quality of life is so much better,” says Jennifer. “If you take someone’s license away and they live in a rural area, for instance, it might even mean they have to move from their family home just because they can’t get their groceries anymore. We don’t want that to happen, but sometimes it does.”

It did to Halifax resident Barbara Mulrooney, a 79-year-old mother and grandmother who speaks on the phone with her daughter every morning. But one day in late July 2015, Barbara wouldn’t answer her daughter’s call.

Later that day neighbours found her unconscious on her bathroom floor, the victim of a stroke diagnosed that evening at the QEII. Barbara considers herself fortunate that the ordeal didn’t impact her more heavily, leaving her left side mildly unsteady.

After 77 days at the QEII's Nova Scotia Rehabilitation and Arthritis Centre she returned home, discovering a month later that she’d been referred to the Driver Evaluation Program. Like most programs of its type it comes at a cost to its participants — $440 in Barbara’s case. After two failed trips with Jennifer, Barbara decided not to be re-tested and voluntarily gave up her license. It was a difficult decision to make.

Barbara counts herself lucky to have a well placed home, a loving family and generous neighbours to make up for her lost license. But in many ways it’s slowed her down and she’s sympathetic toward people in the country whose livelihood is tied to their auto-mobility.

“People can be very devastated when we tell them they’re not going to be able to drive,” says Jennifer. “We’ve seen the whole gamut — grief, anger, sadness.”

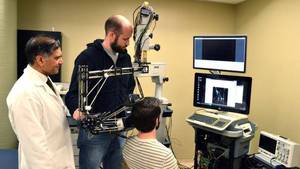

But while Jennifer delivers the bad news she also delivers the good — safely returning Nova Scotians to the road, and in some cases going the extra mile by fitting drivers with specialized equipment so that people with disabilities can get back to driving, restoring the freedom of the open road whenever possible.